Anthony Esolen’s recent article at Crisis, “What Would Our Ancestors Think of Us?” is, well, classic Esolen. He starts by comparing modernity to an open sewer, then imagines a conversation between a modern time-traveller and his ancestors, who despair at the state of things in 2016. “How then shall we live?” Esolen imagines them asking.

Anthony Esolen’s recent article at Crisis, “What Would Our Ancestors Think of Us?” is, well, classic Esolen. He starts by comparing modernity to an open sewer, then imagines a conversation between a modern time-traveller and his ancestors, who despair at the state of things in 2016. “How then shall we live?” Esolen imagines them asking.

In an off-key moment, Esolen notes that now “there are far more women in the workplace than ever before,” and that “we have cracked the back of public racism, so that there are no more segregated hotels or restaurants or schools or businesses.”

I assume Esolen includes these observations as concessions to things modernity has gotten right, though the part about women working might be intended as further indictment. There’s certainly no acknowledgment of the fact that these two (pretty important!) developments would shock and appall many of our ancestors.

If the time-traveler were to show his ancestors a photo of a black family in the White House, does Esolen imagine they would congratulate him? Or would their faces darken as one of them asks, again, “How then shall we live?”

And then there’s this:

There is a country road that straggles its way over a mountain nearby. Lovers go there and pull over at a lookout, where they listen to music and engage in what is called ‘necking.’ It never goes beyond that, because most of them are pretty good kids and understand that bearing children is for marriage, and so is the child-making thing. That understanding allows them to be there in the first place. Innocence – even such compromised and sometimes failing innocence as we possess in a healthy culture – makes for freedom. You will have to tell the audience that there is no necking anymore. You will tell them that, as a rule, it is either sex or nothing. For the worst or the weakest among us, then, there is danger and heartbreak and, eventually, the protective callus of nihilism, even the shedding of blood. For the purest among us, and the most responsible, there is loneliness.

Marvel at that, reader. Seriously, re-read it. Of all the Anthony Esolen paragraphs in the world, it may be the Anthony-Esolen-iest.

As with many of Esolen’s points, it’s mostly disconnected from the real world. In the real world, teenagers are less likely to have sex today than they have been at any point in the past twenty five years. And in the real world, plenty of teenagers were engaging in the ‘child-making thing’ at those lovers’ lanes in the 1950s, when teen pregnancy rates were much higher than they are today.

The problem isn’t just that Esolen is wrong–the problem is that Esolen writes like he doesn’t know a single real, live teenager. Teenagers today don’t ‘neck’? Being ‘pretty good’ means a life of loneliness? I’d love to walk Esolen around the school where I work–a school full of good kids–to see if he could maintain those assertions afterward. Just like I’d love for Patrick Deneen to meet my students and still try to say that they’re “perfectly hollowed vessels, receptive and obedient, without any real obligations or devotions.“

But the thing is, Esolen does know real, live teenagers. He teaches at a university; he has a family. He just doesn’t know real, live teenagers. You get what I mean? His hatred for modernity completely blinds him to the world around him. Which frequently makes his writing, well, kind of silly.

Which is a shame because his question, What would our ancestors think of us?, is a crucial one. I’ve been listening to an audio version of Tiny Beautiful Things, a collection of Cheryl Strayed’s Dear Sugar literary advice columns, on my drive home lately. Last week, I got to the devastating letter written by a man grasping for reasons to go on after losing his 22-year-old son to a drunk driver. “How then shall I live” is a good approximation of the question at the heart of that man’s letter.

Strayed uses her own mother’s death to connect to the man’s grief. “The kindest and most meaningful thing anyone ever says to me,” she says, “is ‘Your mother would be proud of you. Finding a way in my grief to become the woman who my mother raised me to be is the most important way I have honored my mother.”

You all know that in the past few years I’ve lost my mother and both grandmothers. I think about them often. Like Strayed, I think about how to be the person they and the generations before them raised me to be.

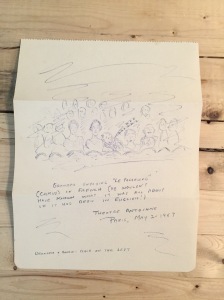

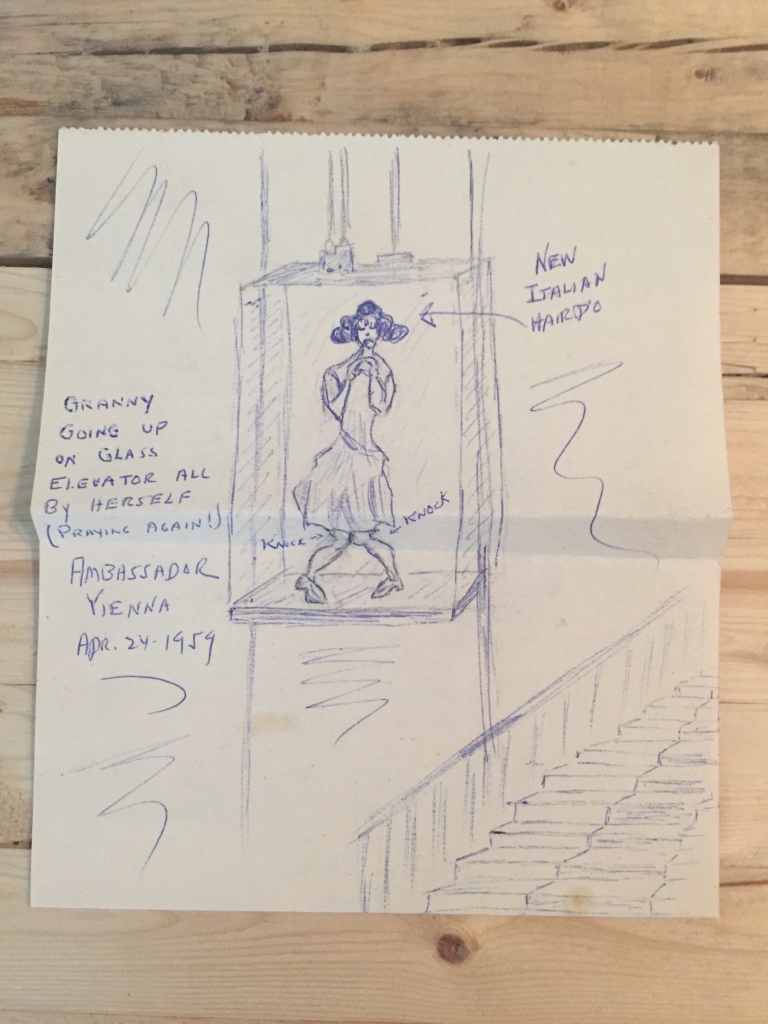

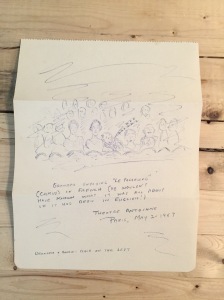

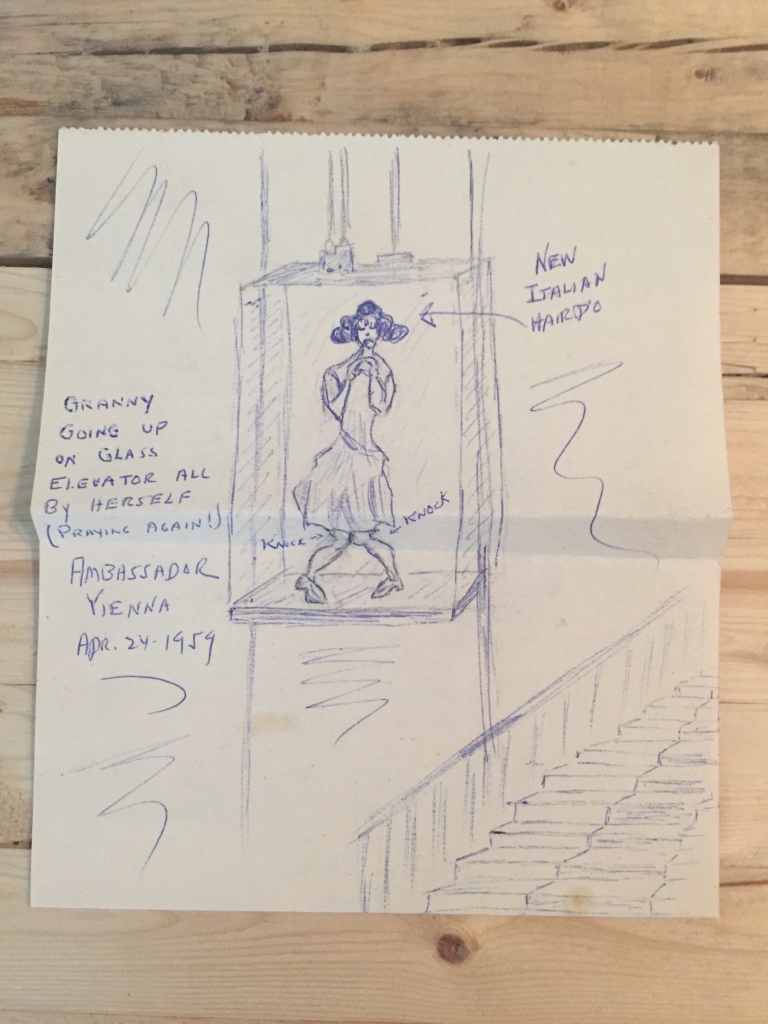

I think about my great-grandfather, too, whom I never met. Recently on Instagram I shared some letters he wrote, with doodles on the back, to my mom while he was touring Europe. I marvel at his voice, his humor, his knowledge of my mom and her interests. And I try to emulate that. Is my love for my daughter as clear to her as he made his love for my mom?

So that question, What would my ancestors think of me?, stays at the front of my mind. It guides how I think, how I parent, how I teach.

But remember, Strayed is writing to a man whose life was centered in his kid. For him, she says, the goal is to “be the man [his son] didn’t get to be,” because “to be anything else dishonors him.” In other words, the influence can–it should— go both ways. We can’t just ask: What would our ancestors think of us? We also have to ask: What will our children think?

When I make Esolen’s question personal, What would my ancestors think of me?, I don’t see a golden past uniting in a line of moral consensus that breaks down in my mom’s generation (or in mine). Instead, I see major disagreements between every generation. Not rancorous disagreements, but big ones, rifts that touch on the core values of race, religion, sex, gender roles, marriage. And I see that, in many of those disagreements, the elder generation was wrong. My mom’s outspoken opposition to racism upset some of her family’s very traditional southern understandings; my grandmother’s gender non-conformity (she was outdoorsy, tomboyish, independent, and raised my mom on her own) troubled my traditional and status-conscious great-grandmother.

To my ancestors’ credit, in many of those generational rifts, the elders recognized they needed to learn from their children. This happened not because they were weak but because they recognized themselves as fallible, and not because they didn’t care about their moral example but because they knew their moral example included the grace of admitting their errors. “He that by me spreads a wider breast than my own proves the width of my own,” said Whitman. “He most honors my style who learns under it to destroy the teacher.”

Unsurprisingly, Esolen uses LGBT issues as the ultimate measure of how far we’ve fallen. Explain Caitlyn Jenner to your ancestors, he says. Explain gay marriage. The thing is, many of us have done just that. After my sister-in-law’s wedding, my grandmother saw pictures online. “I didn’t know [my sister-in-law] had met a man,” she said when she called. She didn’t, I told her. She married a woman. My grandmother paused, and then replied: “Well, I think that’s lovely.”

In other words, when women have a voice in sexual matters, prostitution naturally tends to decline. The same could be said for other conservative freakout-bait, like incest and polygamy. While you may hear advocates for those things using the language of the Sexual Revolution, culturally, those things are less prevalent in modern societies than in traditional ones.

In other words, when women have a voice in sexual matters, prostitution naturally tends to decline. The same could be said for other conservative freakout-bait, like incest and polygamy. While you may hear advocates for those things using the language of the Sexual Revolution, culturally, those things are less prevalent in modern societies than in traditional ones.

Anthony Esolen’s recent article at Crisis, “

Anthony Esolen’s recent article at Crisis, “